Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) is a surgical procedure used to help relieve chronic pain, especially in patients who have not found relief from other treatments. It involves the implantation of a device that sends electrical impulses to the spinal cord to alter the pain signals traveling to the brain.

Functional Anatomy

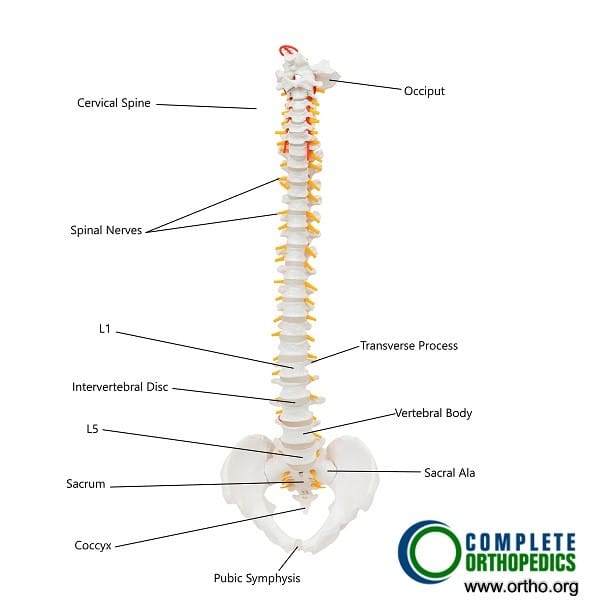

The spinal cord runs within the vertebral column, starting from the base of the brain and extending down the back, ending near the L1-L2 vertebrae. It serves as the main pathway for communication between the brain and the body. The spinal cord sends out spinal nerves that control the movement and sensation in all four limbs and transmit sensory information, including pain, from the body to the brain.

Spinal cord stimulation works by altering the pain signals that are sent from the affected area to the brain, helping to reduce the perception of pain in patients with chronic back pain or radiculopathy (nerve root pain).

Biomechanics or Physiology

The spinal cord stimulator consists of electrodes implanted in the epidural space, which is the space between the vertebrae and the spinal cord’s protective covering. These electrodes are connected to a small pulse generator implanted under the skin, usually in the lower back. When activated, the pulse generator sends electrical impulses to the spinal cord.

The primary mechanism is not to remove the source of pain, but rather to interrupt the pain signals traveling to the brain, thus reducing the perception of pain. The electrical stimulation does not eliminate the source of pain but alters how the brain interprets these signals.

Common Variants and Anomalies

Spinal cord stimulation is typically used for patients with chronic pain that has not responded to other treatments, including medications, physical therapy, and invasive procedures. It is particularly beneficial for patients with conditions such as:

- Failed back syndrome – chronic pain following spinal surgery that did not yield the desired outcomes.

- Degenerative disc disease – wear and tear of spinal discs that causes chronic pain.

- Complex regional pain syndrome – a type of chronic pain that usually affects one limb after injury or surgery.

- Arachnoiditis – inflammation of the protective layers of the spinal cord, leading to severe pain.

In addition, patients with radiculopathy, where nerve compression causes pain radiating from the spine, can benefit from SCS.

Clinical Relevance

SCS is a non-destructive, reversible treatment that has been shown to provide significant pain relief in patients with chronic conditions affecting the spine. This procedure can improve quality of life, reduce dependency on pain medications, and help patients resume normal activities.

Patients who are candidates for spinal cord stimulation generally have persistent pain despite trying conservative treatments, and the therapy is used to manage pain when other treatment options have failed.

Imaging Overview

Imaging plays an essential role in the pre-surgical assessment for SCS, allowing physicians to determine the source of pain and confirm that there is no underlying issue that would contraindicate the procedure. Common imaging methods include X-rays, MRI, and CT scans, which help locate the source of pain, such as herniated discs or spinal stenosis. Imaging also helps guide the placement of the electrodes in the epidural space during the procedure.

Associated Conditions

SCS is particularly beneficial for patients with degenerative spine conditions, radiculopathy, or failed back surgery syndrome. It is also effective in cases of complex regional pain syndrome, where the pain is widespread, and other treatments have not provided relief.

While SCS can be helpful for managing chronic pain, it is not a curative treatment. It is designed to manage symptoms and improve function, allowing patients to engage in daily activities without relying heavily on pain medications.

Surgical or Diagnostic Applications

The spinal cord stimulator is not a first-line treatment but is typically considered after other conservative measures have failed. It is especially useful for patients who have chronic pain that cannot be managed effectively with oral medications or invasive procedures.

The SCS procedure is minimally invasive and can be implanted with small incisions. The device can also be tested via a trial procedure to ensure effectiveness before permanent implantation.

Procedure

The procedure of implanting a spinal cord stimulator first involves the implantation of a trial stimulator under local anesthesia. The trial stimulator involves the placement of an electrode through the skin to the epidural space that is connected to an external generator. The patient returns after a week or so to determine if he would get relief from a stimulator. The time period of the trial stimulator also allows the patient to report any side effects of the stimulation that may warrant not going ahead with the procedure.

The placement of a spinal cord stimulation device involves light anesthesia and the creation of holes in the vertebral structures (laminotomy) to insert the electrodes. The electrodes never touch the spinal cord directly and are placed in the epidural space (space between the vertebrae and the spinal cord lining). The wires go under the skin to attach to the generator which is implanted in the buttock.

Candidates for Spinal Cord Stimulation

Patients with chronic pain in whom all other forms of conservative management have failed may benefit from spinal cord stimulation. The procedure may also help patients suffering from a failed back syndrome who may not benefit from revision surgery. The patients are typically screened for any underlying psychiatric illness and drug addiction. Besides the chronic back pain caused by degenerative arthritis or trauma, patients with conditions such as complex regional pain syndrome and arachnoiditis may also benefit from SCS.

Complications

Commonly patients may report an unusual feeling of paraesthesia upon activating the device for pain. Usually changing the frequency and intensity of transmission may alleviate the symptoms of paraesthesia. As with any surgical procedure, there may be complications of bleeding or infection. Additionally, there may be a complication of leakage of cerebrospinal fluid during the procedure causing frequent headaches.

There may be complications during the procedure such as inadvertent damage to the spinal nerves or the spinal cord from the electrodes which may cause paralysis or numbness of the extremities. There may be battery failure or skin complications from implantation of the generator and electrodes.

Prevention and Maintenance

While spinal cord stimulation offers significant pain relief for chronic conditions, it is not a cure. Patients should continue with physical therapy and lifestyle modifications to help maintain the health of their spine and musculoskeletal system. This includes regular exercise, weight management, and posture correction to prevent the recurrence of pain.

The device itself requires maintenance, including battery replacements (every 2-4 years for non-rechargeable batteries) and periodic adjustments to the electrical stimulation settings based on the patient’s symptoms.

Research Spotlight

A recent study investigated the effects of transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation (tSCS) combined with robotic-assisted gait training (RAGT) on motor and gait recovery in individuals with incomplete spinal cord injury (iSCI).

The randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial demonstrated that the combination of tSCS and RAGT led to significant improvements in lower extremity motor scores (LEMS), gait speed (10MWT), and functional independence (WISCI-II) at one month follow-up. Participants in the tSCS group also showed greater motor strength in knee extensors and ankle dorsiflexors compared to the sham group.

Despite the modest sample size, these results support the potential of tSCS as a promising adjunct to gait training in enhancing motor recovery in iSCI patients (“Study on transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation combined with gait training – See PubMed”).

Summary and Key Takeaways

Spinal cord stimulation is a minimally invasive, reversible treatment option for patients with chronic back pain or radiculopathy who have not responded to other treatments. It involves implanting electrodes that send electrical impulses to the spinal cord, modifying the way the brain perceives pain.

The procedure has shown to provide significant pain relief, improving quality of life, and enabling patients to reduce their reliance on pain medications. It is especially effective for those with degenerative spine conditions, failed back surgery syndrome, and complex regional pain syndrome.

While not a cure, spinal cord stimulation can provide long-term pain relief and functional improvement for many patients, making it a valuable part of a comprehensive pain management strategy.

Do you have more questions?

What is spinal cord stimulation (SCS)?

Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS) is a treatment for chronic pain where a device is implanted to deliver electrical impulses to the spinal cord, modulating pain signals before they reach the brain.

How does SCS work to relieve pain?

SCS works by interfering with the pain signals sent from the spinal cord to the brain. The electrical pulses stimulate nerve fibers, altering how the brain perceives pain, thus reducing discomfort.

What is Failed Back Surgery Syndrome (FBSS)?

FBSS refers to persistent or recurring pain after spinal surgery. It often includes neuropathic pain that originates from damaged or irritated nerves, making SCS a potential treatment for relief.

How is SCS different from other pain treatments?

SCS directly targets the nervous system by modulating pain signals, unlike medications that work systemically or physical therapies that address muscles and joints. SCS also helps patients reduce reliance on medications, especially opioids.

What does the SCS trial phase involve?

The SCS trial involves temporarily placing electrodes on the spine to test if the device provides sufficient pain relief. This trial usually lasts about a week, and if successful (50% pain reduction or more), patients may opt for permanent implantation.

What are the risks of the SCS procedure?

Risks include infection, lead migration (where the electrodes move from their intended position), device malfunction, nerve damage, and the potential need for revision surgery. Approximately 4% to 31% of patients may require revision.

How long does the SCS device last?

The implanted device typically lasts 5-10 years depending on usage. Rechargeable devices tend to last longer but still need periodic replacement when the battery wears out.

Will I feel the electrical stimulation all the time?

With conventional SCS, some patients experience a tingling sensation known as paresthesia. However, newer high-frequency and burst stimulation techniques aim to provide pain relief without the tingling sensation.

Does SCS require maintenance after implantation?

Yes, patients with SCS need follow-up care to monitor the device’s function. The pulse generator may need replacement every 5-10 years, and adjustments to the device’s settings can be made as needed.

Can I still take medications with SCS?

Yes, you can still take medications, but many patients find that they can reduce or eliminate the need for pain medications, especially opioids, after successful SCS therapy.

Can I undergo an MRI with an SCS implant?

Older SCS devices were not MRI-compatible, but many newer models are. However, you must always notify your healthcare provider about the implant before scheduling an MRI, as special precautions may be needed.

Is SCS covered by insurance?

In most cases, SCS is covered by insurance, especially when recommended for conditions like chronic pain or FBSS. However, coverage can vary, so it’s important to check with your provider.